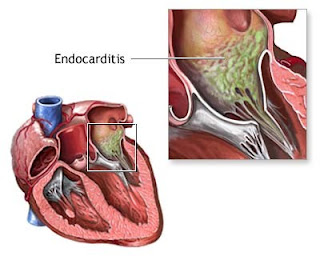

Infective endocarditis is defined as an infection of the endocardial surface of the heart, which may include one or more heart valves, the mural endocardium, or a septal defect. Endocarditis can be broken down into the following categories:

- Native valve (acute and subacute) endocarditis

- Prosthetic valve (early and late) endocarditis

- Endocarditis related to intravenous drug use

Native valve endocarditis (acute and subacute)

Native valve acute endocarditis usually has an aggressive course. Virulent organisms, such as Staphylococcus aureus and group B streptococci, are typically the causative agents of this type of endocarditis. Underlying structural valve disease may not be present.

Subacute endocarditis usually has a more indolent course than the acute form. Alpha-hemolytic streptococci or enterococci, usually in the setting of underlying structural valve disease, typically are the causative agents of this type of endocarditis.

Prosthetic valve endocarditis (early and late)

Early prosthetic valve endocarditis occurs within 60 days of valve implantation. Traditionally coagulase-negative staphylococci, gram-negative bacilli, and Candida species have been the common infecting organisms. Recent data suggest Staphylococcus aureus may now be the most common infecting organism in both early and late prosthetic valve endocarditis.1

Late prosthetic valve endocarditis occurs 60 days or more after valve implantation. Staphylococci, alpha-hemolytic streptococci, and enterococci are the common causative organisms.

Endocarditis related to intravenous drug use

Endocarditis in intravenous drug abusers commonly involves the tricuspid valve. S aureus is the most common causative organism.

Pathophysiology

Infective endocarditis generally occurs as a consequence of nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis, which results from turbulence or trauma to the endothelial surface of the heart. Transient bacteremia then leads to seeding of lesions with adherent bacteria, and infective endocarditis develops.

Pathologic effects due to infection can include local tissue destruction and embolic phenomena. In addition, secondary autoimmune effects, such as immune complex glomerulonephritis and vasculitis, can occur.

Frequency

United States

Incidence is 1.4-4.2 cases per 100,000 people per year.

International

Incidence of disease appears to be similar throughout the developed world.

Mortality/Morbidity

- Increased mortality rates are associated with increased age,2 infection involving the aortic valve, development of congestive heart failure, central nervous system (CNS) complications, and underlying disease such as diabetes mellitus. Mortality rates also vary with the infecting organism and seem particularly higher when Staphylococcus aureus is the infecting organism.1,3

- Mortality rates in native valve disease range from 16-27%. Mortality rates in patients with prosthetic valve infections are higher. More than 50% of these infections occur within 2 months after surgery.

Sex

The male-to-female ratio is approximately 2:1.

Age

Although endocarditis can occur at any age, the mean age of patients has gradually risen over the past 50 years. Currently, more than 50% of patients are older than 50 years.4

Mendiratta et al found that, in their retrospective study of hospital discharges from 1993-2003 of patients aged 65 years and older with a primary or secondary diagnosis of infective endocarditis, hospitalizations for infective endocarditis increased 26%, from 3.19 per 10,000 elderly patients in 1993 to 3.95 per 10,000 in 2003.5

Mendiratta et al found that, in their retrospective study of hospital discharges from 1993-2003 of patients aged 65 years and older with a primary or secondary diagnosis of infective endocarditis, hospitalizations for infective endocarditis increased 26%, from 3.19 per 10,000 elderly patients in 1993 to 3.95 per 10,000 in 2003.5

Clinical

History

- Present illness history is highly variable. Symptoms commonly are vague, emphasizing constitutional complaints, or complaints may focus on primary cardiac effects or secondary embolic phenomena.

- Primary cardiac disease may present with signs of congestive heart failure due to valvular insufficiency. Secondary phenomena could include focal neurologic complaints due to an embolic stroke or back pain associated with vertebral osteomyelitis.

- Fever and chills are the most common symptoms.

- Anorexia, weight loss, malaise, headache, myalgias, night sweats, shortness of breath, cough, or joint pains are common complaints.

- As many as 20% of cases present with focal neurologic complaints and stroke syndromes.

- Dyspnea, cough, and chest pain are common complaints of intravenous drug users. This is likely related to the predominance of tricuspid valve endocarditis in this group and secondary embolic showering of the pulmonary vasculature.

Physical

- Fever, possibly low-grade and intermittent, is present in 90% of patients.

- Heart murmurs are heard in approximately 85% of patients. Change in the characteristics of a previously noted murmur occurs in 10% of these patients and increases the likelihood of secondary congestive heart failure.

- One or more classic signs of infective endocarditis are found in as many as 50% of patients. They include the following:

- Petechiae - Common but nonspecific finding;

- Splinter hemorrhages - Dark red linear lesions in the nailbeds

- Osler nodes - Tender subcutaneous nodules usually found on the distal pads of the digits

- Janeway lesions - Nontender maculae on the palms and soles

- Roth spots - Retinal hemorrhages with small, clear centers; rare and observed in only 5% of patients.

- Signs of neurologic disease occur in as many as 40% of patients. Embolic stroke with focal neurologic deficits is the most common etiology. Other etiologies include intracerebral hemorrhage and multiple microabscesses.6

- Signs of systemic septic emboli are due to left heart disease and are more commonly associated with mitral valve vegetations. Multiple embolic pulmonary infections or infarctions are due to right heart disease.

- Signs of congestive heart failure, such as distended neck veins, frequently are due to acute left-sided valvular insufficiency.

- Splenomegaly

- Other signs

- Stiff neck

- Delirium

- Paralysis, hemiparesis, aphasia

- Conjunctival hemorrhage

- Pallor

- Gallops

- Rales

- Cardiac arrhythmia

- Pericardial rub

- Pleural friction rub

Causes

- Native valve endocarditis

- Rheumatic valvular disease (30% of native valve endocarditis [NVE]) - Primarily involves the mitral valve followed by the aortic valve

- Congenital heart disease (15% of NVE) - Underlying etiologies include a patent ductus arteriosus, ventricular septal defect, tetralogy of Fallot, or any native or surgical high-flow lesion.

- Mitral valve prolapse with an associated murmur (20% of NVE)

- Degenerative heart disease - Including calcific aortic stenosis due to a bicuspid valve, Marfan syndrome, or syphilitic disease

- Approximately 70% of cases are caused by Streptococcus species including Streptococcus viridans, Streptococcus bovis, and enterococci. Staphylococcus species cause 25% of cases and generally demonstrate a more aggressive acute course.

- Prosthetic valve endocarditis

- Early disease, which presents shortly after surgery, has a different bacteriology and prognosis than late disease, which presents in a subacute fashion similar to native valve endocarditis.

- Infection associated with aortic valve prostheses is particularly associated with local abscess and fistula formation, and valvular dehiscence. This may lead to shock, heart failure, heart block, shunting of blood to the right atrium, pericardial tamponade, and peripheral emboli to the central nervous system and elsewhere.

- Infection that occurs early after surgery may be caused by a variety of pathogens, including S aureus and S epidermidis. These nosocomially acquired organisms are often methicillin-resistant (MRSA). Late disease is most commonly caused by streptococci.

- Endocarditis associated with intravenous drug use

- This condition most commonly involves the tricuspid valve, followed by the aortic valve.

- Two thirds of patients have no previous history of heart disease and no murmur on admission. A murmur may not be heard in patients with tricuspid disease because of the relatively small pressure gradient across this valve. Pulmonary manifestations may be prominent in patients with tricuspid infection: one third have pleuritic chest pain, and three quarters demonstrate chest radiographic abnormalities.

- Diagnosis of endocarditis in intravenous drug users can be difficult and requires a high index of suspicion.

- S aureus is the most common (<50% of cases) etiologic organism. Other causative organisms include streptococci, fungi, and gram-negative rods (eg, pseudomonads, Serratia species).8 Methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) accounts for an increasing portion of S aureus infections and has been associated with previous hospitalizations, long-term addiction, and nonprescribed antibiotic use.

- Healthcare-associated endocarditis

- Endocarditis may be associated with new therapeutic modalities involving intravascular devices such as central or peripheral intravenous catheters, rhythm control devices such as pacemakers and defibrillators, hemodialysis shunts and catheters, and chemotherapeutic and hyperalimentation lines.4

- These patients tend to have significant comorbidities, more advanced age, and predominant infection with Staphylococcus aureus.

- The mortality rate is high in this group.

- Fungal endocarditis9

- Fungal endocarditis is found in intravenous drug users and intensive care unit patients who receive broad-spectrum antibiotics.

- Blood cultures are often negative, and diagnosis frequently is made after microscopic examination of large emboli.

- Diagnosis: Definitive diagnosis of infective endocarditis is generally made using the Duke criteria. Major criteria include (1) multiple positive blood cultures for the infecting organism and (2) echocardiographic evidence of endocardial involvement or a new regurgitant murmur on physical examination.

EmoticonEmoticon